For ardent theatergoers, there may always be something strangely, though movingly, Sphinx-like about an art gallery: the figures in the pictures talk to no one, and do not know we’re there. Sunday’s creators built this tension into their show another way as well-simply by deciding to make a play out of a painting in the first place. Sondheim has written about his newfound pleasure in “allowing songs to become fragmentary, like musicalized snatches of dialogue,” without the “static verbosity of recitative.” Sondheim’s fragments work like Seurat’s dots they index both the energies of isolation and the elusive possibilities of harmony, of coalescence. In Sunday, though, the lovers’ subtler sunderings become the template for all the tensions and contentions among the lesser characters: the fights and slights out of which Sondheim and Lapine shape a bright kaleidoscope of songs. Lovett crooning her ardor to Sweeney Todd as he, simultaneously, sings a love song to his razor).

Out of such crossed purposes gorgeously vocalized, Sondheim had shaped wonderful thwarted-love stories before (think of Mrs.

The art of stillness shakespeare how to#

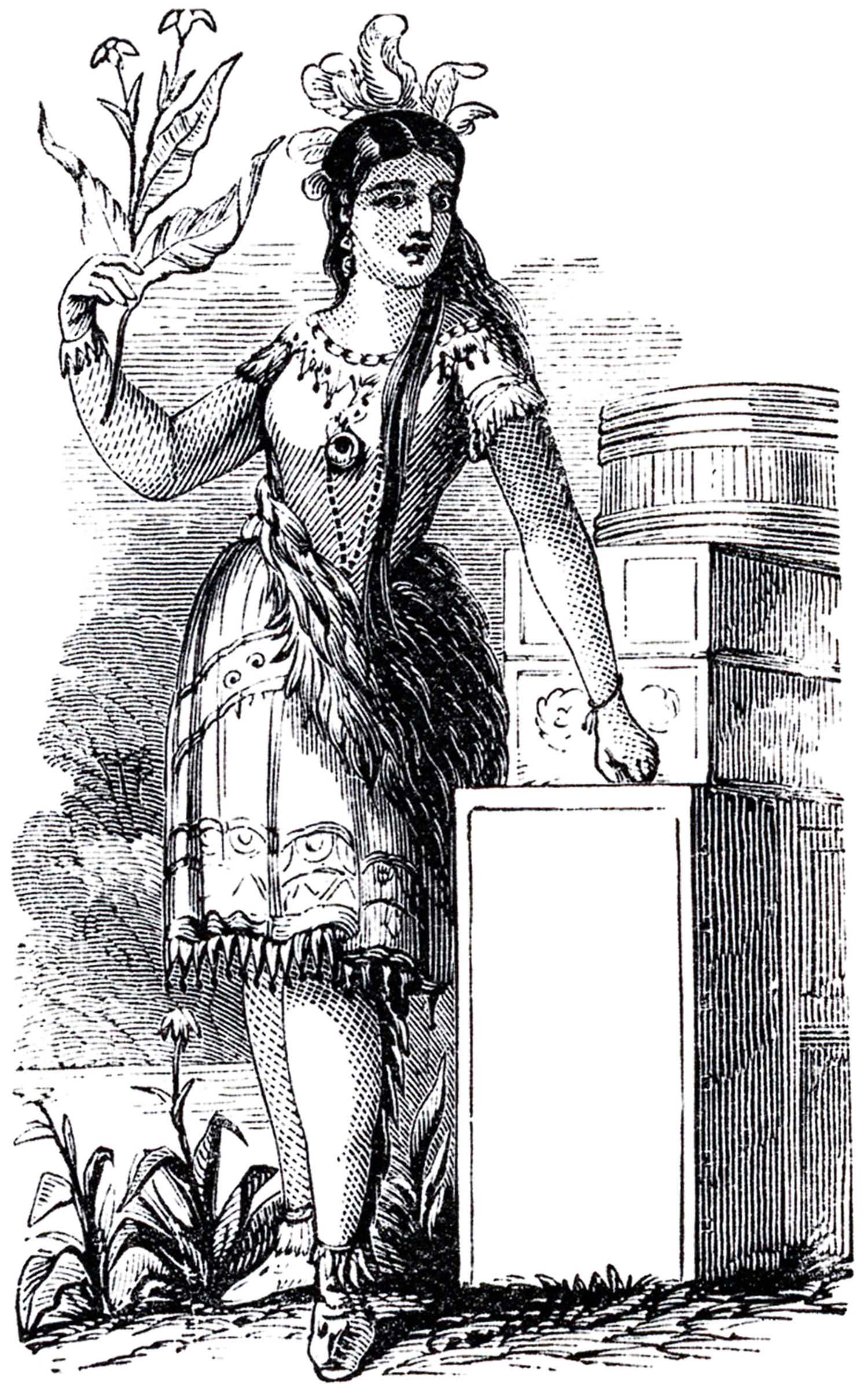

In later songs we learn that George, while not oblivious to her wish that he look past painting into passion, knows nothing of how to fulfill it, or even how to want to: his painting is his passion distraction might do it damage. In the show’s first song, we see her locked into the pose George has assigned her, while going volubly, silently, and hilariously crazy at the disparity between her atomization as an aggregate of dots obsessively stippled onto canvas, and her actuality as the complex flesh-and-blood woman she’s longing for her lover to see.

She is Seurat’s exuberant, exasperated mistress, muse, and model. As opening gambit in that splendid game, Sondheim and Lapine name their fictive female protagonist Dot. Sunday in the Park with George incarnates these tensions in its characters’ intrinsic isolation, and in their baffled, variable desire for convergence. There’s the tension that shapes the show: between the impassioned pursuit of harmony (a key word in the script from start to finish) and the welter of missed connections that make deep harmony barely attainable in art, nearly impossible in life. He was struck by “the curious fact,” as Sondheim later put it, “that of all the fifty-odd people” in this large luminous image of a community at play, “not one.is looking at another.” Everyone’s assembled no one quite connects. At a moment catalytic for the show’s conception, Lapine saw that the same principle, operating virtually in reverse, governs the gazes of the figures in the picture. What’s most famous about the painting (as Chicagoans know well) is the innovative relation of parts to whole: all those hundreds of thousands of dots, insistently separate when seen close up, coalesce into passages of shimmering color when viewed from the right remove.

Thirty years or so ago, Stephen Sondheim and librettist/director James Lapine spent days at the Art Institute of Chicago, gazing at the painting on which they hoped to base this show: George Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte–1884.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)